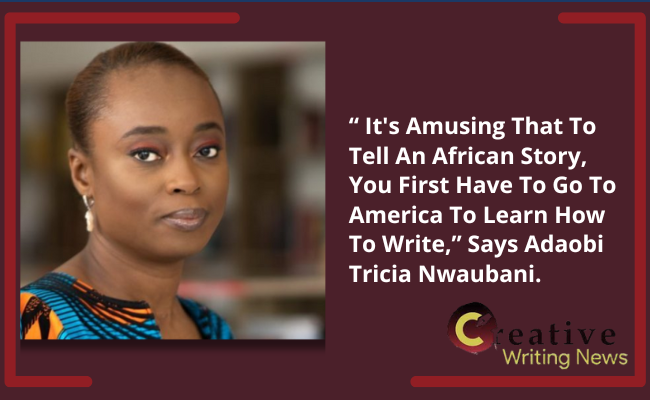

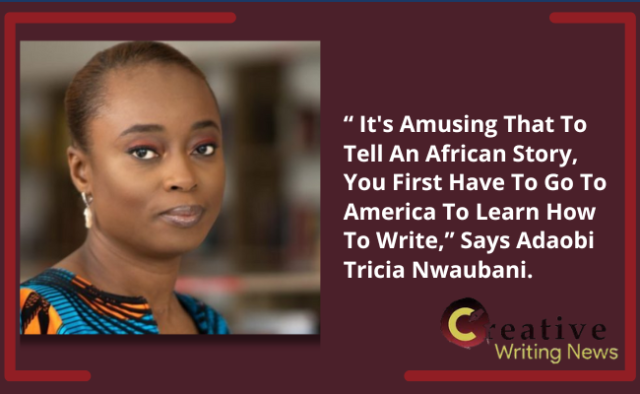

“ It’s Amusing That To Tell An African Story, You First Have To Go To America To Learn How To Write,” Says Adaobi Tricia Nwaubani.

Chijioke K. Onah, writing for Contemporary Literature, recently published a 24-page interview with Adaobi Tricia Nwaubani, author of I Do Not Come to You by Chance and Buried Beneath the Baobab Tree.

The interview highlights important subjects such as the influence and writing of the 2018 novel Buried Beneath the Baobab Tree, and the growing trend of African writers seeking MFA (Master of Fine Arts) programs in Creative Writing or related fields, particularly in the Western world.

But, many literary stakeholders have asked, what is wrong with young African writers seeking creative writing training in foreign institutions?

“Of course, there’s nothing wrong with formal training in any endeavor one wishes to pursue, but the African case appears quite extreme.” Adaobi says in the interview, “I am arguably the only African writer on the global stage with no formal training or advanced degree in writing. It’s not so with writer communities in other parts of the world. With the writers based in places like Nigeria, I suspect that it may have something to do with the desire for connections. Many locally based writers seem to see creative writing courses that usually invite foreign-based writers as part of the training team—as a means of making connections that could lead to a referral to an agent or publisher.”

Does an African Writer need an MFA to succeed?

The obvious answer is No. However, there is no denying the rising interest in these programs. MFA application webinars and mentoring sessions are becoming common in the African literature spaces across the continent. And for every writer who makes a Twitter post about their acceptance into an MFA program, there are countless more waiting and aspiring to get admitted into a prestigious school. If the end goal of the MFA program for African writers is to get connections, how authentic would the African story be? Would they appeal only to Western audiences?

As African writers fight to secure foreign publication, the stories risk being controlled by Publishers in London and New York decide which African writers to give contracts to, which of our stories will see the limelight, according to Adaobi. This means that narratives might cater more to Western tastes than to the lived realities and perspectives of African audiences. This is also a general problem often seen in the books written by writers in the diaspora, from poorly described staple foods like the jollof to details that play a major role in the everyday lives of the African continent. Adaobi makes mention of a bestselling novel she read that put her off because of wrong writing.

“In that book, one of the major characters was telling his mother, “I’m too old to believe in ghosts.” No! No African would utter that comment in the eighteenth century because they did believe in ghosts. The typical African, especially of that time, believed that there is a spirit world. You believed that your ancestors can come back. So even the Africans who are telling African stories a lot of times are inauthentic.”

With the recent casting announcement of Nigerian-American author Tomi Adeyemi for her fantasy Children of Blood and Bones, the internet sparked with outrage, reigniting dialogues on the issues of writing about Africa by people outside of Africa, especially those who have not lived there in a long time. Oftentimes, the role of the West can be seen in the publication of these books. Africa is a trend, something to be read about regardless of its accuracy. In an age where diversity is an important term, the culture of a whole continent is reduced only to stories that the West can empathize with.

‘They also control the awards. It is, as you mentioned, those who get canonized in the West that we now take seriously back home. And we all pretend that we are in charge of African literature?’ asks Chijioke Onah in the interview with Adaobi Nwaubani.

Author Adaobi Tricia Nwaubani says her simple solution is that you can write for a global audience from Africa and by simply being African.

‘I don’t need to act like an African. I am African. Simple and short. I believe in Africa. I don’t need to prove it.’

Perhaps the main question should be, ‘Has Africa ever truly been in charge of African literature?’

Historically, the publishing scene in Africa can be traced to the influences of Christian missionaries. According to a Read African Books article on Publishing in Africa, “Printed books became widespread in Africa with the arrival of European missionaries, primarily for purposes of religious conversion, heralding the advent of colonialism.” Not only that but even as our literacy rate began to grow all around the continent, foreign publishers still maintained a dominance over the industry, determining who and what got published. How different is it for Africa today?

Thankfully, we now have publishing houses in Africa, such as Masobe Books, Narrative Landscape, Kwani Trust, and Cassava Republic, prioritizing local stories making books more accessible and affordable for the average African. However, the challenge of gaining recognition from international literary institutions remains.

Adaobi Tricia Nwaubani claims, “Judges in the United Kingdom and United States decide which of our books will receive awards. The West crowns the authors that we celebrate in Africa. Our literature will never be “free” until we take control of this process.”

One of the key criteria for an MFA is having a strong writing sample and portfolio. Still, for many African writers, the best chance at recognition comes from being published in foreign literary magazines. This reliance on international platforms highlights the issue that African literature is still heavily influenced by Western institutions. From deciding which books receive awards to shaping the narratives that gain global traction, the West continues to be the gatekeeper of African literary success.

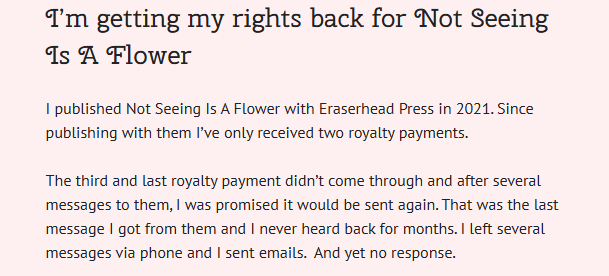

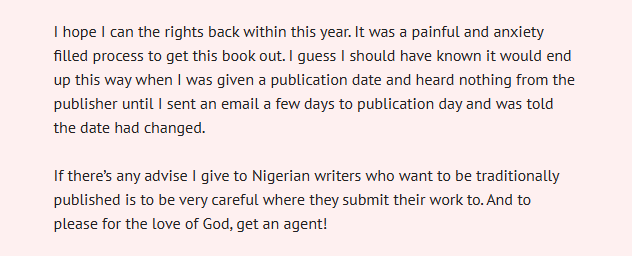

Beyond recognition, money–and access to it–is an issue Adaobi Tricia Nwaubani does not touch on. Many African writers struggle to receive payments from foreign publishers and magazines, a challenge worsened by local financial systems that are incompatible with international transactions. A recent example is Erhu Kome, Author of The Smoke that Thunders and Not Seeing is a Flower, who recently put out a post highlighting her struggle with collecting royalty for her book from her US Publishers. Such experiences highlight how there are still barriers even after securing a foreign publishing deal.

The West cannot be blamed if African writers put their opinions on a pedestal, seeking spots on MFA programs and telling stories they feel will grant them better chances at international publishing. A degree from a prestigious institution like Iowa often lends credibility to writers on a continent where foreign praise is seen as a mark of excellence. However, Adaobi Tricia Nwaubani overlooks the reality that African writers need to survive, pay bills, and secure their future. With limited opportunities locally, these programs become a practical way to secure a future

What, then, is the solution to the growing trend of African writers seeking MFA programs?

As Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie once advised a group of African writers, it is important for writers to gain real-world experiences before choosing to start an MFA program because living in the real world helps shape writers’ perspectives. If one is to keep writing about Africa, then one should learn more about Africa—the countries, the backgrounds, tribes, languages, histories, and most importantly, the cultures. Then, you can proceed to acquire the formal training you want to help shape your stories better.

Furthermore, schools in Africa should work on establishing MFA in Creative Writing programs. With an abundance of writers on the continent, one would think there would be African versions of this important qualification to help writers write about their home rather than from continents across the seas.

“It’s amusing that to tell an African story, you first have to go to America to learn how to write.” Says Adaobi Tricia Nwaubani.

Ultimately, the future of African literature lies in fostering confidence among writers to create without foreign influences dominating their acquisition, production, and storytelling processes. As more African writers turn to MFAs and Western recognition for opportunities, should the African literary community be concerned about the authenticity and direction of African Literature? What are your thoughts on Adaobi Nwaubani’s view of the African writers’ MFA pursuit as extreme?