Ngugi wa Thiong’o Books: Marxism in ‘Cultural Narcissism’ of Anti-Pan Africanist Gikuyu Literatures

Book lovers all over the world love Ngugi Wa Thiong’o books and work. A quick Google search of the term, ‘Ngugi wa Thiong’o Books’ reveals the fact that he has readers in every part of the world. But kind of literature does he put out into the world?

Our guest contributor, Alexander Opicho, believes that this prolific writer produces Marxist literature. Can most ‘Ngugi wa Thiong’o Books’ be categorized as Marxist literatures? And why?

In this article, Alexander Opicho treats us to an analysis of all ‘Ngugi wa Thiong’o ‘Marxist’ body of works.

Ngugi wa Thiong’o Books: Marxism in ‘Cultural Narcissism’ of Anti-Pan Africanist Gikuyu Literatures.

Apart from the River between and Weep Not, Child all other Ngugi Wa Thiong’o books are out-right Marxist literatures, in fact some of them read like the pamphlets of a communist party, or like socialist essays in the Pravda, the Russian Newspaper during the Soviet era.

Thus, Ngugi can be said to be an African writer that has been guided by Marxist ideology. The quality of Marxism that guides him may be non-scientific breed of utopian or prosaic socialism, but all the same, his works mainly communicated socialist ideals.

Thus, criticizing or appreciating Ngugi’s intellectual work must be done under the contextual light of Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o being an ideologue that is expected to relate with his ideology of socialism in a way to prove it a revolutionary praxis.

My Introduction To Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o Books.

Personally, I first met with Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o through reading his Detained, Writers in Politics and then the Petals of Blood. This was towards the end of the last century; this was also the time when Kenya was wiggling and socially wangling under the heavy burden of political dictatorship of the ethnic type left behind by Jomo Kenyatta only to be extended through the Nyayo philosophy of Daniel Moi.

Hence, reading Ngugi Wa Thiong’o books at that time was so comforting and inspiring. It was also a moment of good coincident, to be living in troubled space of political dictatorship and to be reading highly spirited political writers like Ngugi.

It was a very fruitier exercise that worked as a socle on which is the wall of my revolutionary consciousness that led me to further intellectual venturing into savouring Frantz Fanon, Aime Cesaire, Jean Paul Sartre, Amilcar Cabral, Jawarlal Nehru, Nyerere, Kwame Nkrumah, Mamdan, Mao’s Selected Works, Antonio Gramsci, Rosa Luxembourg, Lenin, Trotsky, Samir Amin, Liebknecht, Engels and then volume one of Marx’s Capital.

I read these writers in a span of two decades, now I look back at that time as season of my intellectual experience that formed my Marxist mind. Since then; I have always understood that not all those claiming to be Marxists are consciously Marxist. An issue which Karl Marx dealt with by declaring utopian and prosaic Marxism as some kind of intellectual chaff to be differentiated from the functional scientific Marxism.

The point to note is that there is no any other brand or breed of Marxism that can work apart from scientific Marxism.

The Role Of Language In Writing About Marxist Ideologies.

Good and effective use language that can be understood by the working masses is one of the perspectives of the scientific brand of Marxism.

Thus, any practicing Marxist that is scientific in orientation chooses language for his or her revolutionary activities with focus on the revolutionary conditions and the revolutionary challenge at hand.

Language that dignifies ethnic identity of the revolutionary is not a priority, but that language which works well in pushing forward the revolutionary agenda to a wider scale is the language to be given priority for use in all the processes of revolutionary communication.

This is why Karl Marx, a German-Jew, brought up speaking Deutsch, as his vernacular, went to school speaking Deutsch and was taught at all levels in Deutsch, chose to teach himself English and thence write in English when he was contracted to contribute weekly essays to the New-York Tribune.

These are the essays that were later on published as Revolution and Counter Revolution, a tomelet of kind among other tomes of literary work by Marx. Logic behind all these was Marx’s considerate assessment of revolutionary work and challenge at hand.

Emotions of cultural chauvinism that could have probably seduced Karl Marx to write in his native Deutsch or ethnic Hebrew did not come up, courtesy of good level of revolutionary consciousness with focus on liberating the people suffering under intellectual oppression or political Tyranny without necessarily consider the ethnic looses and gains that go with the machineries of communication.

Morality of critical arguments leveled against Ngugi in this article is based on the fact that there is no any intent to perpetrate any kind of dissing acts against Ngugi’s literary work, other than ideological obligation to uphold Fanon’s revolutionary logic that a non-innocent bystander is either a coward or a betrayer.

Personally, I am not innocent; I cannot chose to be a bystander watching Ngugi wa thiong’o mislead a non-suspecting audience with his leather-tongued arguments that African revolutionaries are supposed to communicate in their rural vernacular languages. No, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o is wrong.

The context of Africa’s social and economic conditions cannot allow Ngugi’s vernacular philosophy to work. African countries can work well with National languages, and Africa as a continent needs pan-African language which can facilitate un-fettered communication among African societies and as well as enable Africa to communicate with natives of African-Caribbean, natives of African-American, natives of African-Australian and natives of African-European communities.

I mean Black people all over the world need to communicate with one another through writing and speaking. The current African social and cultural dynamics favor Kiswahili to work as a Pan-African language in the Sub-Saharan Africa, and then Arabic to be used as Pan-African language in the Saharan Africa.

If educational, Mass Media, diplomatic and family institutions in Sub-Saharan Africa can be facilitated to learn and use Kiswahili, and the same to be done with Arabic in Saharan Africa then it will be very easy to achieve dialogic relations among African countries.

Communication and Dialogic relations are one of the guiding philosophies of Pan-African movement. Unfortunately, wasting our energy in the nostalgia for the languages we spoke before colonialism will not help us achieve the Pan African dialogic boon we are bound enjoy if at all we can put our energy in developing institutionalization of Kiswahili.

It is under this light that this article is morally bound to kowtow, perhaps with trepidation, before the throne of salutary and noble choices by those organizations and countries that have adopted Kiswahili as their language of learning.

Particularly, one cannot afford to miss making salutary mention of Tanzania and South Africa for their respective heroic recognition and institutionalization of Kiswahili culture, Kiswahili education and Kiswahili language, for no other reason but out of positive spirit for Pan-Africanism.

Let me use my country Kenya to make a comment about the nature of national languages we need in our African countries; technically African countries are bound to use their local industrial languages, industrial languages are also known in the world of literature as ‘urban vernacular’. Urban vernacular is any language used by workers in the factories, streets, police cells, mine-fields, hostels, lodgings and any other place a common man works for bread.

Urban vernacular can be slang language but as long as it is serving the purpose of communication among working masses then that it is the linguistic sub-culture of the working population, the nation must go by it. May be comparative learning from creative language and Caribbean poetry by Kamau Braithwaite will be helpful in this juncture.

In his books History of the voice and also Nation Language, Dr. Kamau luridly communicated that literatures from post-colonized and ex-enslaved societies need not to be extremely Eurocentric. They must substantially reflect historical heritage and consciousness of the people.

This is why the language in Kamau’s poetry was adjusted to sycorax and reggae in order to reflect Caribbean people’s emotional intelligence and as well as self-awareness under the light of history and disruptive geopolitical experience of the Afro-Caribbean world.

Thus, it’s has to be pointed out that today’s sociology of Marxism and literary anthropology will well recognize Kamau’s Sycorax, Jamaica’s reggae language and Kenya’s Sheng as urban vernaculars to be embraced by their countries for domestic communication, either for the purpose of literature , politics or commerce.

Politically important to the subaltern experience is the social efficacy in the adoption and use of urban vernaculars in ameliorating negative ethnic dynamics.

My social experience in Kenya’s urban life is the fact that urban vernaculars are beneficial in the political sense that they are very effective in helping the post-colonized countries like Kenya to overcome pitfalls, trials and tribulations of ethnic consciousness.

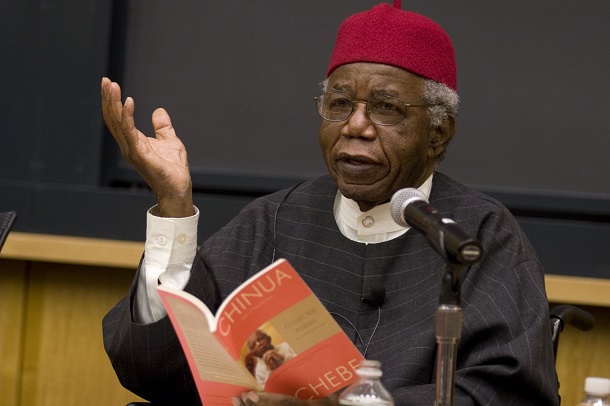

Achebe in the Education of a British Protected Child under chapter on politics of language dismissed Ngugi for having no reason and cultural logic to switch from writing in English to writing in Gikuyu. Ngugi’s argument that ‘English is the language of the colonizer and hence it is cultural alienation for the colonized to write in English’ does not make any sense to Chinua Achebe.

Instead, Achebe extents his logic of language used in Things Fall Apart and Ant-Hills of the Savannah to encourage African writers to use European languages in the manner that serves well explanation and expression of African thoughts within Africa and outside Africa.

Staff Photo Nick Welles/Harvard News Office

In the book, Chinua Achebe is very out-right in appreciating the fact that English and other European languages to facilitate communication between different African communities.

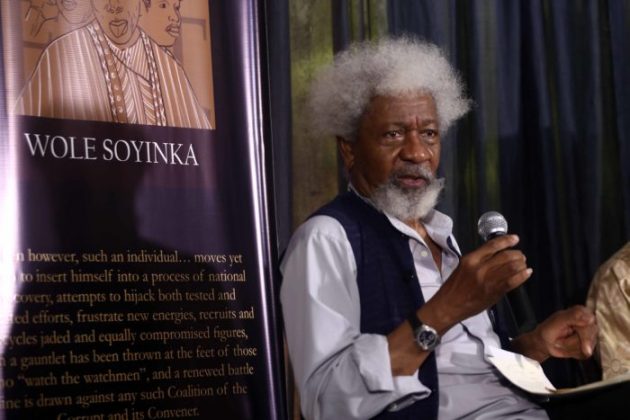

For example the only way Ngugi can communicate with Wole Soyinka or George Lamming is through English language. The role of European languages facilitating communication among African countries as well as other parts of the world is a fact which makes Politics of language in Africa to put most of Marxist scholars into an ambivalent state when they read Karl Marx’s statement in volume one of Capital that ‘colonialism was to some extent a necessary evil to Africa’. But anyway, that is that.

Economics of literature teaches that writing is a business, and it is done with a focus on the market. All books are written to be sold for revenue generation to the Author. And hence, identification of the book market makes a superior economic sense than cultural and ethnic identity in writing.

Logic of extension under this situation will readily show that the Gikuyu reading population is not a logical market for Ngugi’s books, Ngugi’s market is the English speaking world. Hence, his switching from writing in English to writing in Gikuyu was very illogical in economic sense.

However, this contradiction in economic logic is may be attenuated by a lived paradox that Ngugi wa thiong’o, the respected global-scale crusader for writing in Gikuyu is holding a well paying job as the distinguished and passionate professor of special English at California University in Irvine.

It is paradoxical that Ngugi wa thiong’o does not teach Gikuyu literature at Karatina University in Central Kenya. May be a curious mind in the future will ask that how did Ngugi wa thiong’o expect Gikuyu literature to be established, yet he was significantly absent from its institutional praxis?

In early 2017, I met Professor Chris Wanjala at the Senior Members Common Room at the University of Nairobi to have a cup of tea as I listen to him talk about literature in the English speaking world.

Professor Wanjala avoided talking about Ngugi wa thiong’o books, until I propped him to talk about Wole Soyinka’s palpable low opinion about novels by Ngugi, Ngugi’s mission to write in Gikuyu, and Ngugi’s open sensual gratification in regard to his four children trying to be writers but not other young writers from Africa.

Wanjala breathed in deeply, made a last sip at his tea, he told me to finish mine so that we could walk across the campus to the University Printer. We were out of speculative ear-shots;

Chris Wanjala made the following observations which I am quoting from memory:

‘Wole Soyinka as a human rights crusader used to organize public demonstrations agitating against Kenya government of that time to release Ngugi from detentions. Wole Soyinka’s pressure was among the efforts that helped in getting Ngugi released.

But later on, Ngugi wrote in the Home-Coming that Wole Soyinka was a metaphysical poet. That was somewhat a derogatory remark made out of Ngugi wa thiong’o’s un-guarded ‘intellectual Narcissism’-intellectual self-love. From then Wole Soyinka chose to ignore Ngugi.

Ngugi’s literary socialization has been full of ‘cultural Narcissism’- Ngugi wa thiong’o has loved his Gikuyu culture more than literary and cultural logic allows. Ngugi’s thrasonical praise of his children by telling the Saturday Nation in Nairobi that his children are the best young writers from Africa is just a narcissistic affair which can be confirmed by evidently pointing out that Africa has a lot of young writers doing better than Ngugi’s four children.

Ngugi’s pushing for writing in Gikuyu is Cultural Narcissim influenced by an intention to mock (like the ethnic mockery in the irritatingly Gikuyu speech on acceptance of the 2020 Catalonya art prize) other Kenyan communities by alluding to Kenya’s political history where the Gikuyu community has produced three presidents that have rule Kenya for thirty years within the fifty years of Kenya independence from the British colonizers’.

One can go ahead to test intellectual validity and credibility of Chris Wanjala’s observations, this can easily be done by examining Ngugi’s contemporary intellectual relation to other African writers.

I have tried to do the same, starting with how Ngugi thought about Dr. Kamau Brathwaite.Ngugi’s funeral Speech in respect of Kamau as a voice of African Presence was and still is available online as a Youtube clip evident of Ngugi’s selfish thinking about the intellectual giant in the station of Dr Kamau Braithwaite, the thinking was just in terms of Ngugi’s wife, Ngugi’s mother and Ngugi’s new baby called Mumbi.

Another useful evidence of ‘cultural narcissism’ in Ngugi’s literary socialization can be read in his recent article; Securing the Base published online in the Journal of African Cultural Studies edited by Carl Coetzee. It is a very long article discussing African indigenous languages as the base to be secured before going ahead to learn other languages; it is a very inspiring article.

However, in this article Ngugi was overtaken by a Narcissistic syndrome to quote his son Mukoma wa Ngugi in each and every fifth paragraph in the article, in between Ngugi quotes his own books.

It is so interesting that Ngugi did not mention any other writer or language scholar from Africa in this article. This does not mean that there are no young writers of language and literature in Africa.

There are very many, in the likes of Afua Cooper from the Caribbean, Bamboo Soyinka from Nigeria and Australia, Ken Walibora from Kenya, Ogot Benge from Uganda, Muchaparara Musemwa from South Africa, Dr Chilala the Zambian onasmastician, and many others from all over the world including Austin Bukenya and Timothy Wangusa the two literary age mates of Ngugi.

Why Ngugi chose to cull his contemporaries and other productive young African scholars by avoiding to mention them in his article on the language as the cultural base was a selfish act done out of his sharp and mature instinct of narcissism, but nothing else.

Alexander Ernesto Khamala Namugugu Islam Opicho is a Kenyan essayist, poet, short story writer and feminist – human rights crusader living and working in Kenya. His work has appeared in the BUWA journal’s sixth edition on women and Migration, Queer Africa 2, Awaaz Magazine, Nairobi Law Monthly, Management Magazine, the Bombay Review, the East African, the Daily Nation, East African Standard, the Monitor, Pambazuka Magazine, Sahara reporters African Literature Today (ALT 37), African HAIKU, and the Kalahari Review. His research and writings are focused on multidisciplinary approach to protection of fundamental human rights. He is guided by a philosophy that human diversity is a praxis that derives strength from freedom of thought and expression.

Pingback: How To Overcome Writer’s block {10 Tips + Personal Examples} - Creative Writing News